“Producti-what?” I’m glad you asked!

Before I explain myself, let me clarify: It is most probably a non-existing word that has been used as clickbait. It seems to have worked – since you are here.

To make some sense, I need to give some context first: Today’s product industry has been hugely influenced by authors shaping the Silicon Valley product space. A good example is Marty Cagan, who popularized the concept of the “Product Operating model”, a set of principles that have sparked a transformation, shifting product development from a Design-first approach to a Product-first new philosophy, redefining how organizations approach innovation and user-centric solutions. Once the almost exclusive driver of innovation and product creation, Design is now part of a larger product ecosystem, with increasing responsibility and influence placed in the business representatives.

The jury is still out on whether this is a positive transformation in the long run. Nonetheless, this is the reality for many of us working in the industry, regardless of where we are and our organization’s maturity. As William Gibson once wrote, “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed”. It is likely that, sooner or later, your organization will be impacted by this transformation.

At Laerdal Medical, a global healthcare education and quality improvement service provider, we are undergoing such a transformation. We are the leader in the healthcare education sector, have a wide product portfolio that covers the totality of the circle of learning, close to a hundred designers from multiple disciplines (Research, UX, Industrial, Visual, and Service), and product development sites across Europe, Asia, and America. Amid the transformation, we have implemented all principles of the product operating model: empowered cross-functional teams owning each product, product trios (Product, Design, Engineering), periodic OKRs processes focused on outcomes (and not outputs) and focus on continuous discovery and delivery.

“But what has all of this to do with DesignOps?”

You are KILLING IT with these questions!

Let me explain it. There is a link. I promise.

It became a priority to bring alignment and drive the effectiveness of our product development processes while trying to escalate to different organizational structures. Basically, to focus on operationalizing those processes, including design, became necessary and not a nice-to-have endeavor. Hopefully, many of you can relate to this.

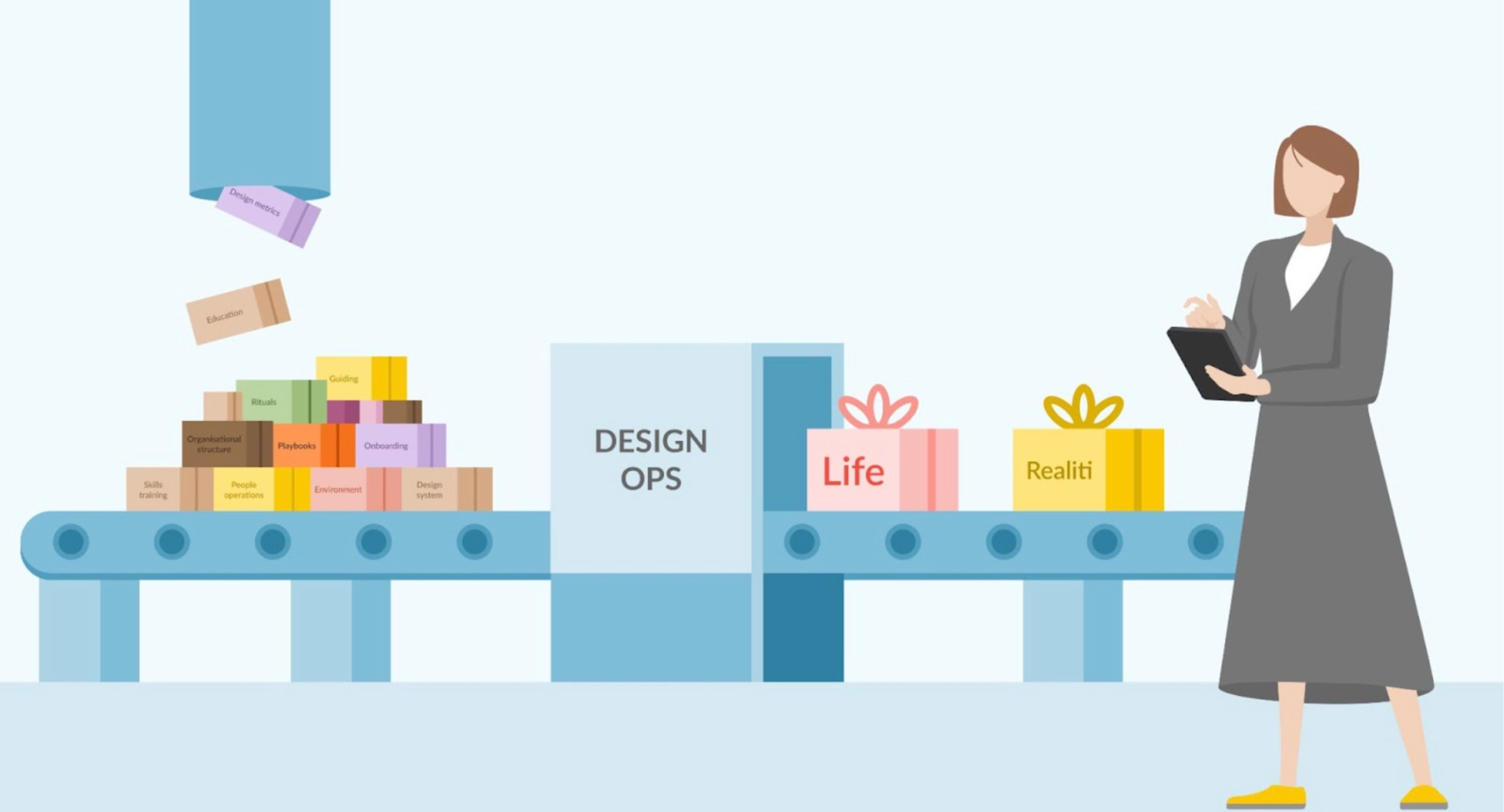

Enter DesignOps.

If you are reading this, you are probably familiar with the concept of Design Operations, but in case you aren’t, I fully recommend the NN Group article about it. Or, as Frog Design defined the term in their DesignOps 101 article, “like DevOps, which has revolutionized the development process with an agile, iterative approach, DesignOps allows organizations to rapidly scale and iterate design processes across teams”.

Now, even acknowledging that DesignOps is needed, implementing it in a company with many teams and designers is not without its challenges. For once, it is not possible to enforce DesignOps. True, long-lasting change rarely comes from a top-down approach.

Having top-down support and buy-in is impactful, but it needs to come from within to make a proper behavior change in our teams. DesignOps is, additionally, a quite new discipline whose impact and value can be difficult to measure, and lack of clarity of impact tends to not go well in senior leadership minds. Although gains in efficiency are key arguments for it, the lack of direct revenue connection makes DesignOps an effort easier to de-prioritize.

So, to get enough buy-in and support from leadership and ownership from our product teams, we took a page from the emerging discipline of “Product Management”, got inspiration from the Product Operating Model, and decided to treat DesignOps initiatives as products (or more precisely, capabilities, as they have internal customers).

Did you see it? I told you there would be a connection, and it only took about 600 words to get there.

“And what does that mean?”

Well, it means many things, but one key result is a shift in the direction of the efforts. DesignOps has traditionally been a support function that pushes guidelines, best practices, and processes to the teams. Looking at them as capabilities implies that teams are now pulling value out of them instead. This new dynamic doesn’t imply less overall effort but a change of direction from the DesignOps team to the product teams. If the DesignOps capabilities don’t offer enough value to the teams, they will not use them. But if the value is there, they can become ambassadors and drivers of true, long-lasting change of behavior in the organization.

“I see. And how do we get there?”

It is not an easy road, but as I mentioned, we took a page from the Product Operating Model and implemented some key behaviors and mechanisms that, in time, produced the shift. But the first step was to create the actual products, starting with two: (1) We started our design system and called it Life. It is not only a set of Figma components but a comprehensive single source of truth for our brand, physical and digital artefacts (including code), and marketing and communication efforts. (2) We also collected different initiatives towards operationalizing our design research activities and called it Realiti (not a typo, I promise), where we aim to provide a coordinated research experience underpinned by ethical privacy practices and impactful tools, delivered as a service that facilitates producing and sharing insights, making them accessible to everyone across the organization.

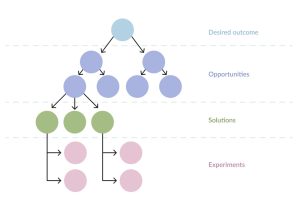

In the Product Operating Model, all products have outcome-oriented goals, and as we do with our customer-facing products and internal capabilities, we use OKRs as a goal-setting framework for our DesignOps ones. It stands for Objectives and Key Results. It expresses, ideally in a narrative way, a team’s goal (objective)—why we are doing anything—and then states measurable outcomes (key results) that demonstrate if the goal has been achieved, setting up the success criteria. There is a lot of information about OKRs and their advantages, so I will not get into that. Let me just say: They are not easy but worth the effort.

The important part of this is the shift toward outcomes (measurable changes in behaviors). Instead of building feature upon feature, product teams focus on what change they want to achieve, measure it continuously, and then freely explore the best way to achieve it. It makes it much easier to understand why you are building what you are building, and it also empowers the team to decide how to achieve the goals. And that is what we want to capitalize on in the DesignOps space.

Since we have set upon building a design system capability and a research service, we focus our outcomes on usage and satisfaction. To measure our efforts, we defined success as product teams using our capability and service and how satisfied they are with our offer. Very much like a product. Now, there are many KPIs you can define, but the intention behind our choice was to ensure that we are delivering something of value. If our internal customers can’t see enough value in using our offerings, they won’t. They are not forced to do it, so we need to be sure that they see value in them, use them (usage), and are satisfied with them (CSAT – Customer Satisfaction). There are other relevant metrics, too, but we decided to work on mainly these two to stay focused.

For example, in the case of our research service (Realiti), an important component is the creation of a participant’s network (a group of people, users, and customers of our products interested in participating in research activities). We want to measure how many participants we recruit, and it is important but not an outcome metric. We could end up with thousands of participants, but if your teams don’t use them as part of the service, we would have achieved nothing. Granted, the more participants we have, the higher the likelihood our teams will be able to use the network, but the number is not the important goal; it is a way to achieve our actual goal: teams using Realiti.

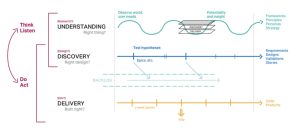

Having outcome-oriented goals is a great start, but it is not enough. It has also been important to adjust the way we work, once again, inspired by the same principles that shaped modern product development. So, instead of big implementation efforts and long change management efforts, we prioritize quick wins and continuous improvement fueled by continuous discovery and learning from our internal customers. It is a fine line to walk, and we have reverted to bigger initiatives several times as it is not that easy to limit the scope of our efforts when operationalizing our ways of working. Nonetheless, the mantra is to prioritize time to impact and deliver value to our internal customers as fast as we can. A bit less value, but delivered earlier, can have a bigger impact on changing behaviors. Although this has been beneficial to our DesignOps initiatives, securing ongoing support from leadership, this strategy is something every organization should adjust to its own reality, experimenting and iterating with different cadences and scopes. At the end of the day, the purpose is to ensure we deliver value to our internal customers as quickly and reasonably as possible.

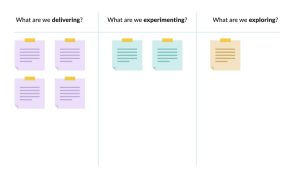

The thing is that once you start delivering on a quicker cadence, expectations are created. And with expectations comes potential friction. We found transparency to be the most effective tool to minimize that friction and potential frustration. Transparency is usually delivered in the form of a clear roadmap, but roadmaps are easily misused and can become traps that create feature teams instead of empowered ones. At the same time, roadmaps are great communication artifacts that we want to leverage. The solution was to create a dynamic living document that would clearly state what the teams are working on in three different groups:

- The stuff we are delivering now – Internal customers can expect to get access to these in a short time

- The experiments we are running – A subset of customers may be trying some of these

- The opportunities we are further exploring – A subset of customers is participating in research activities

At the time of this article, the DesignOps teams are experimenting with this setup, but we believe there is enough potential to use this roadmap as a communication piece while still keeping enough flexibility to pivot and experiment as needed.

“I see. You are indeed treating DesignOps initiatives as products. But what have you achieved with this?”

You are clearly on fire. And to be honest , that is the most relevant question.

Productifying DesignOps initiatives is not a one-and-done process but a transformation effort. There is a change of behavior for both the teams working on these initiatives, and the internal customers used to have Ops teams unloading guidelines and best practices over them.

It is still early in the process, but we have seen a shift in our positioning with leadership as it has become easier to communicate the goals and impact of these initiatives. By “speaking” the language of products, we also communicate better with product teams who now understand better the value of using our capabilities. It is also easier now to track and measure success. Granted, treating DesignOps initiatives as products is not a must, but the frameworks and ways of working with products facilitate the creation of outcome-oriented goals and speak of the impact we are creating, not the outputs we are delivering.

All of that is great, but the biggest change we have experienced is within our own DesignOps teams. This has forced us to focus on the impact and needs of the organization instead of pushing forward the “design agenda”. Not to say that we don’t aim for great design and research and to foster the value and impact of design, but we do it by ensuring that the value we deliver is so evident that teams have no reason not to use our capabilities. That small shift in the direction of the relationship between the DesignOps team and the product teams ensures we focus on the most impactful initiatives and keep us honest, focused, and constantly engaged with our work and the impact we deliver.

And that, at the end of the day, is worth the effort.

* * *

*Illustrations by the wonderful Yuliia Kosheva (unless otherwise stated).

Website: https://laerdal.com/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/hector-mejia/